The historic AI deal has skeptics in Hollywood. Some worry that if digital copies and synthetic performers are legalized, it may lead to a decline in employment opportunities for those in the performing and support industries. Hollywood risks becoming overrun by synthetic performers if famous actors and their AI clones can appear in multiple films simultaneously, pushing out up-and-coming actors.

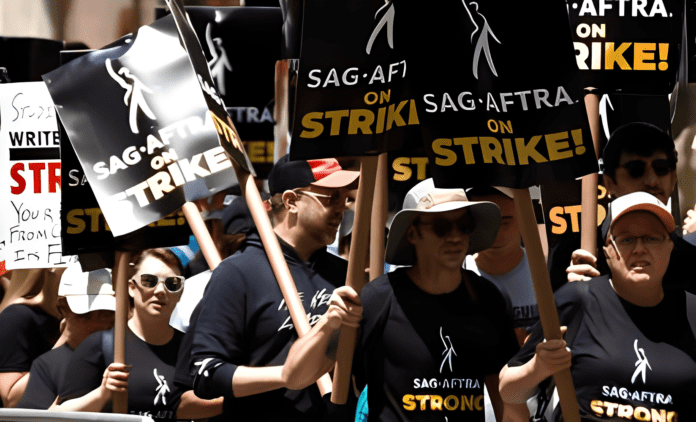

14% of the SAG-AFTRA Artists national board voted against submitting the agreement for approval to the entire membership due to the strong feelings around it. On the other hand, the AMPTP agreements were unanimously approved by the Executives of both the Directors Guild of America (DGA) and the Writers Guild of America (WGA), who instructed their members to accept them.

The unauthorized use of a tool capable of learning to write or change scripts created by humans was an attempt by writers to obtain control of this technology through their agreement with AMPTP. The possibility that AI might steal actors’ likenesses was a major concern for them during the talks. Sustaining one’s existence requires stringent limitations. “In this agreement, there are indeed a lot of imagined uses going forward, both for minor characters, major characters, and background actors,” remarks Joshua Glick, visiting associate professor at Bard College. “That is part of why there’s maybe more anxiety surrounding where the actors stand with AI versus the gains made for the writers.”

One of the most outspoken critics of the deal is Justine Bateman, who plays the role of Family Ties and serves as an AI advisor to the SAG-AFTRA bargaining committee. She wrote in a widely read X thread in the days after SAG and the AMPTP reached a tentative agreement, “Bottom line, we are in for a very unpleasant era for actors and crew.”

Bateman is mainly worried about the provisions of the agreement that deal with “synthetic performers”—artificial intelligence designed to seem like people. “This gives the studios/streamers a green light to use human-looking AI objects instead of hiring a human actor,” she stated in an X post. “It’s one thing to use [generative AI] to make a King Kong or a flying serpent (though this displaces many VFX/CGI artists); it is another thing to have an AI object play a human character instead of a real actor.” She argued that this would be the same as if the Teamsters had agreed to let their employer use autonomous trucks instead of union drivers.

A further issue is regulating the characteristics of these “synthetic performers.” The new agreement states that “if a producer plans to make a computer-generated character that has a main facial feature, like eyes, nose, mouth, or ears, that looks like a real actor, and they use that actor’s name and face to prompt the AI system to do this, they must first get permission from that actor and agree on how this character will be used in the project.”

If a studio blatantly infringes an actor’s right of publicity, which is frequently called likeness rights, the actor can utilize this to protect their reputation. But what if the performers weren’t Denzel Washington but had the gravitas of the actor? Is it possible to call it a “digital replica,” the kind of thing that requires permission to use according to the contract? How well can an actor explain away more mysterious traits? Studios can use the analogy between AI performers and young actors to train their AI, similar to how a large language model “digests” great works of literature to influence the text it generates. This could give them some legal leverage.

What would happen if we defined an actor as being only a human being in the 2023 TV/Theatrical Contracts tentative agreement? SAG-AFTRA Chief Negotiator @DuncanCI provides important context. More details & voting info are available at https://t.co/qtezCsrzzs. #SagAftraStrong pic.twitter.com/p5kuv5mvfj

— SAG-AFTRA (@sagaftra) November 29, 2023

“Where does the line between a digital replica and a derived look-alike that’s close but not exactly a replica lie?” wonders David Gunkel, a professor specializing in AI in media and entertainment at Northern Illinois University’s Department of Communications. “This is something that’s going to be litigated in the future, as we see lawsuits brought by various groups, as people start testing that boundary because it’s not well defined within the terms of the contract.”

There have been additional expressions of worry regarding the vagueness of certain language in the contract. “If they would be protected by the First Amendment (e.g., comment, criticism, scholarship, satire or parody, use in a docudrama, or historical or biographical work).” Studios are required to acquire permission only in certain cases. Studios may get around permission requirements by passing off use as satirical and using the US Constitution.

Consider the arguments around digital alterations, especially the question of whether or not a copyright is required when “the photography or soundtrack remains substantially as scripted, performed, and/or recorded.” Glick suggests that this may necessitate a change in one’s attire and hairstyle as well as a change in one’s facial expression or gesture. This raises the question of how AI will affect acting: Will there be anti-AI protests similar to Dogme 95 or will performers begin watermarking performances that do not use AI? (The arguments surrounding CGI in this sector are nothing new.)

The precarious position of performers makes them vulnerable. In the future, actors may need AI approval and replication to pay their expenses. Actor inequality is likely to deteriorate as well, with wealthy opponents of AI projects potentially enjoying special treatment and famous people who consent to being digitally recreated having the opportunity to “appear” in multiple projects simultaneously.

Just with the WGA agreement, this one “puts a lot of trust in studios to do the right thing.” Maintaining dialogue between labor and capital is its primary goal, he asserts. “It’s a step in the right direction regarding worker protection; it does shift some of the control out of the hands of the studio and into the hands of the workers unionized under SAG-AFTRA,” said Gunkel. “I do think, though, because it is limited to one contract for an exact period of time, that it isn’t something we should just celebrate and be done with.”