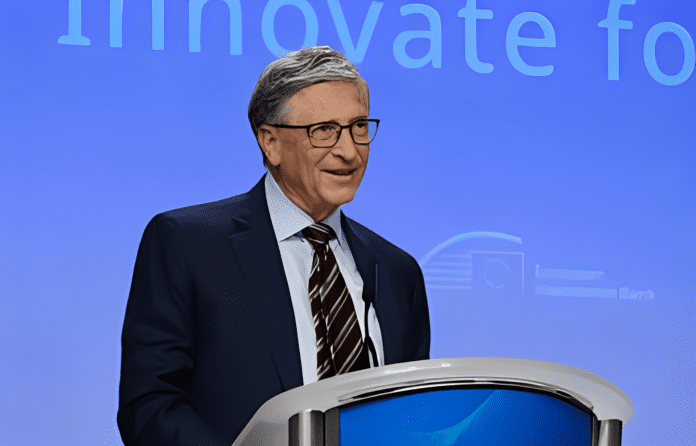

For the first time this year, I put AI to practical use in my job, rather than treating it as a fun toy. For many others, I imagine the same is true. A massive technological shift is just starting to take place right now. The future of artificial intelligence (AI) is both exciting and perplexing, with many questions still unanswered. However, the potential of AI to boost efficiency and increase accessibility to healthcare, education, and other services is more apparent than ever before.

One fundamental principle has always guided my work: innovation is the driving force behind advancement. I started Microsoft because of this. I co-founded the Gates Foundation with Melinda Gates over twenty years ago for this same reason. So much progress has been made in people’s lives during the last century because of this.

The global infant mortality rate has been nearly halved since the year 2000, with innovation playing a significant role in this remarkable achievement. Researchers developed more efficient and less expensive methods of producing vaccines without compromising safety. They improved vaccines against dangerous infections like rotavirus and found new ways to deliver them, allowing them to reach more children in more distant areas of the world.

When resources are few, you have to be creative to make the most of what you have. The secret to making the most of every dollar is innovation. The velocity of new discoveries is set to be accelerated at a level never seen previously by AI.

So far, the development of new medications has been one of the most significant effects. AI techniques have the potential to greatly accelerate drug discovery processes; in fact, several businesses are now developing cancer treatments using these methods. Addressing health concerns like AIDS, tuberculosis, and malaria, which disproportionately affect the world’s poorest, is a significant objective of the Gates Foundation in AI.

In my opinion, low- and middle-income countries have a lot of untapped potential when it comes to artificial intelligence (AI). While in Senegal not long ago, I had the opportunity to meet with several inventors hailing from underdeveloped nations. They hope that the incredible artificial intelligence work they’re doing will help their local community members in the future. They are laying the groundwork for a huge technological boom later this decade, even if most of their work is in its infancy.

Witnessing the level of innovation being discussed is very remarkable. I met several groups that are investigating the potential of AI to fight antibiotic-resistant bacteria, improve HIV risk assessment, increase access to medical records for healthcare providers, and many more. The innovative solutions proposed by people in developing nations to some of the most pressing problems in their home country astound me.

One woman dies every two minutes during pregnancy or childbirth, which is a terrible statistic to consider. An Indian group plans to employ AI to boost their chances. When it comes to high-risk pregnancies, ARMMAN’s huge language model will eventually be a helpful companion for medical professionals. You may use it whether you’re a novice nurse or a seasoned midwife; it adapts automatically to your level of experience, and it’s available in Telugu and English.

Projects of this nature have a lengthy path ahead of them. There are still a lot of challenges to overcome, like making sure projects can scale up without compromising quality and making sure they have enough access to the backend to stay operational.

We need to address some of the more general concerns about AI, such as how to avoid bias and hallucinations, if we want to make the most of them. In a medical setting, a hallucination could occur when an AI system asserts something with complete certainty that is not true. I disagree with the researchers who claim that hallucinations are an inevitable consequence of AI. In time, I believe it will be possible to train AI models to differentiate between fact and fiction. As an example, OpenAI is making encouraging strides in this area. (To be completely transparent, Microsoft is both a main investor and a partner of OpenAI.)

Also, we need to make sure that AI products are designed with the end users in mind. As an example, I’m really looking forward to using Somanasi, an AI-powered school coach. Somanasi, meaning “learn together” in Swahili, will deliver the benefits of the AI teaching tools that are now being piloted to students in Kenya. These tools are mind-blowing since they are personalized to each learner. Students will feel more at home with it because of its familiarity and its alignment with local curricula and cultural backgrounds.

The number of scholars considering the best ways to introduce cutting-edge electronics to nations with poor or medium incomes is encouraging. Artificial intelligence has the potential to create a fairer world if we allocate wise funds today. The gap between the developed and developing worlds in terms of access to innovations can be narrowed or eliminated. In my opinion, widespread adoption of AI will not occur in high-income nations like the US for at least another 18 to 24 months. I anticipate a similar degree of utilization in African nations in around three years. While there is still some lag time, it is significantly lower than the lag times experienced with previous advancements.

To lessen global inequality, closing this gap is essential. Thinking about how AI can be utilized to provide revolutionary technology to those in need at a record-breaking pace gives me hope for the future, even in the face of adversity.