The UK Supreme Court affirmed earlier decisions by rejecting a request to identify artificial intelligence as “an inventor in a patent application.” Technologist Dr. Stephen Thaler wanted his artificial intelligence (AI) Dabus to be acknowledged as the creator of “a food container and a flashing light beacon.”

However, in 2019, the IPO turned this down, stating that only a living individual may be designated as an inventor. The Court of Appeal and the High Court later upheld the decision. The IPO has maintained, and courts have agreed, that only “persons” and not AIs can have patent rights.

Five Supreme Court justices have rejected an attempt to overturn earlier verdicts, ruling that “an inventor must be a person” and that an AI cannot be identified as an inventor to gain patent rights.

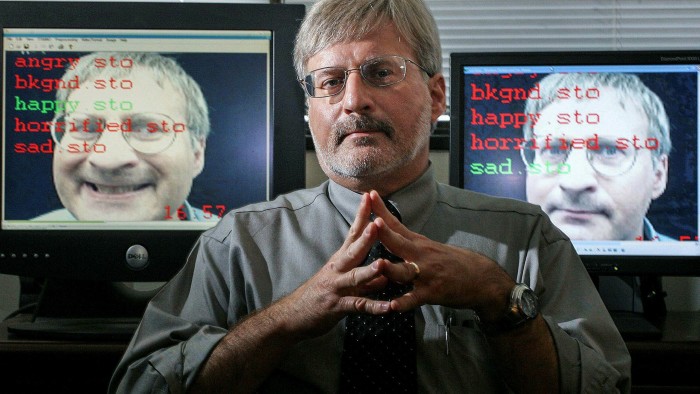

Dr. Thaler, who believes Dabus is a “conscious and sentient form of machine intelligence,” told the BBC, “Naturally, I feel disappointed by this decision, highlighting the ongoing clash between human and machine intelligence.”

The IPO informed that it was pleased with its decision and explanation. However, it made it clear that “the government will nevertheless keep this area of law under review to ensure that the UK patent system supports AI innovation and the use of AI in the UK.”

“The judgment does not preclude a person using an AI to devise an invention – in such a scenario, it would be possible to apply for a patent, provided that person is identified as the inventor. The judgment alludes that had this been the scenario it had been asked to consider, the outcome may have been different.” Rajvinder Jagdev of specialist intellectual property litigation company Powell Gilbert said.

Legitimate concerns

Additionally, Dr. Thaler’s claim that, as the owner of the AI, he should be granted patents on Dabus’s ideas was denied. A different ruling may have resulted in “headaches for companies using [AI] software to innovate as they may not be the owner of the patent,” according to Diego Black of European intellectual property company Withers and Rogers.

The decision presented “interesting policy questions” regarding how governments would try to amend legislation in the future as AI advances, according to Simon Barker of legal firm Freeths.

“Similar debates exist in other areas of intellectual property rights as well.” Copyright, for example, in AI-generated works. Is the AI’s programmer the creator, or is it the user who commands the machine? And what if it’s only the machine, as Dr Thaler stated about Dabus?”

However, Professor Ryan Abbott of the University of Surrey, who represented Dr Thaler in the case, stated that the ruling meant that “AI, at best, can be a ‘highly sophisticated tool’ that people who invent can use.”

“This affects the meaning of an “inventor” under UK patent law, and to be an inventor, one need not make the creative leap behind the invention, as had been previously assumed. Accordingly, companies who use AI to develop products will have to say they or their employees are the inventors, even when the humans involved do little else but switch on the computer.” As AIs become more capable of producing fresh ideas autonomously, several legal experts predict that pressure to revise existing rules will grow.

The IPO said it acknowledges “that there are legitimate questions as to how the patent system and indeed intellectual property more broadly should handle [AI] creations.” The UK government submitted a response to the “consultation on AI and intellectual property” in June 2022.

The IPO stated, “The response concluded that there should be no legal change to UK patent law now, and noted that many share the view that any future change would need to be at an international level. The decision of the Supreme Court does not alter that conclusion.”